February 3, 2026 | Source: MAARIV

Art is the only language we speak. It's irrelevant where everyone came from

"Art is the only language we speak. It's irrelevant where everyone came from."

A group of eight artists, Jewish and Arab, and one artist, from all over the country, gathered in Givat Haviva for three months of creating and living together in one space. Now, when their exhibition comes up, they talk about cross-fertilization

By Ofer Livnat

02/03/2026

Residency | Photo: Thala8Gallery

"It really appealed to me to be part of a team again. I felt that for a long time during the creative process I was alone with myself in the studio. I wanted to be part of a social environment, a human environment. That's what brought me here," says Chen Heifetz, an actor and performer who routinely lives and works in Tel Aviv, but for the past three months has been living with eight artists, Jewish and Arab, in one area in Givat Haviva in the Menashe Regional Council.

Nine artists, all but one of whom are women, were selected to participate in the residency program of the Joint Center for the Arts in Givat Haviva for a period of five months, of which they lived and created together for three months. Last week, they packed up their belongings and returned to their homes, and now their exhibition, "There Is No Space Between Us," is on display at the Givat Haviva Art Gallery (a grand opening will be held this Friday).

Chen Hefetz | Photo: Noga Davis

The nine artists came from different parts of the country: Tel Aviv, Daliyat al-Carmel, Haifa, Jerusalem, Araba, Nof HaGalil and Ra'anana. They stayed together in one space 24/7, and throughout the entire period they were accompanied by the head of the program, an artistic mentor, a social facilitator and a team of mentors made up of prominent artists. They also went on inspirational tours and discussions at art institutions, were exposed to contemporary artistic initiatives, and led three art events.

Similar and different

Heifetz, the oldest of the group, 36, is referred to by the participants as "the father of the show." In his work, he traces the story of his family that came from Algeria. "I came here as part of building my personal process," he says. "I heard about this program, which has a lot of mentoring, a lot of support, and of course funding. It's significant."

Wasn't it difficult to live for three months with strangers?

"Of course it is. The difficulty was mainly before, thinking 'What, am I going to live with someone in a room one meter by one meter now?' And I'm also the only son on the show. I have to say that these fears lasted only a few days. We actually arrived, and very quickly a dynamic of mutual responsibility, of openness was created – both to get to know and to dive into each other's worlds. We're very involved in other people's projects, and it's a lot of fun. Of course, challenges arose along the way."

Oil paints on tablecloth | Photo: Chen Hefetz

What challenges?

"Personally, my first challenges were not related to the team, but to living. I don't get along here in the dining room, I realized that on the first day. I immediately gave it up."

Were there cultural difficulties? Gaps between Jews and Arabs?

"There were these little things of life, of food, of cleanliness. Here the gaps and of course language gaps were most expressed. When native Hebrew speakers speak to each other in Hebrew, or when Arabic speakers speak to each other in Arabic, that's one thing. But when you talk together, it's not 100% in terms of expressive abilities. This highlighted how essential language is to communicate. When you think about it at the level of the place we live in, it's very strange that they know Hebrew from home, they've been learning all their lives, and we don't know Arabic."

Has the situation in the country had an impact?

"There's some magic to this show, it's really one of the most tight and sealed bubbles I've ever lived in. Partly because this space in Givat Haviva is completely utopian, and also because we are here with some intensity around our works, around art. Most of the time I didn't even remember that there was a world outside of our environment here. Art is the only language we speak, and it unites us all. It's irrelevant where everyone came from."

Indeed, it is evident that art has succeeded in connecting the participants. Faiza Badarna, a 25-year-old multidisciplinary artist from Araba, says that at first she only wanted to work with art, and it was difficult for her to connect with others, but later she received support from them that helped her with the project. "They would come to my studio and sit with me, and we would talk for hours about the project and about life," she says. "I feel that in recent times we have all become good friends, and there is a very strong connection between us. We're not alike , everyone comes from a different world, and I think that contributed to our art."

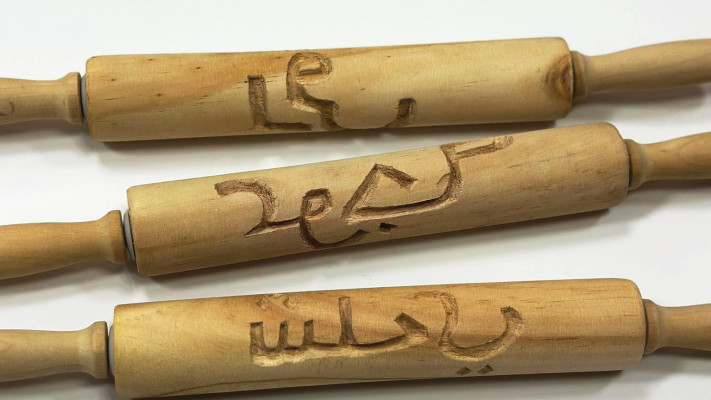

Wood carving. Faiza Badarna | Photo: Faiza Badarna

What is it like to be 24/7 with people you didn't know?

"At first it was a little difficult. I wanted to paint and let them leave me. Sometimes I wanted to go out and breathe and come back, and I could do that. In the end, I started talking to everyone, sharing and getting out of this corner of mine."

In her project, Badarna dealt with memories related to her home. She chose four objects, each with a personal story: a rolling pin, an oven spoon, a mortar and a blue wallet. "I took the rolling pin and began to remember those moments when we were all together – me, my sister and my mother," she explains. "When we talk and laugh together, and we cry together. I remembered the words my mother used to tell us, like 'press the dough well,' and I started carving them on the rolling pins. As long as I carve I remember my mother, her inner world."

Faiza Badarna | Photo: Noga Davis

Aluma Fishman (26) is a creator in Jerusalem. Here she presented a series of photographs documenting her activities in the "Standing Together" movement. "I was looking for an artistic space where I would only engage in art and not be in the race for life," she says. "I was born in Turkey, my parents worked there, so I have some background in Islamic culture. I also have good friends there, so I'm right on the line. On the show, we're a distinctly female majority, and we're very similar, we all love the same fields in a big way, we hear the same music, we watch the same series. At first I might have thought I was coming to a place with people who were different from me, but in practice it didn't feel that way."

Alona Fishman | Photo: Noga Davis

Did the shared space in the studio help your creation?

"I think it gave me more courage because there's a safe discourse here about politics and opinions that are a little closer to mine. It gave me more courage to do it without apologizing."

Have friendships been formed here that will continue after the end of the program?

"Sure, it's also inevitable. We live together for three months, day and night. We eat together, prepare meals, watch movies, talk about art."

What do you hope will come out of here?

"When I arrived, I really hoped I would have a new piece, and it happened. I hope I will continue with it. Maybe also collaborations with those who are here."

Not about the conflict

Anat Lidror, director of the residency program and curator of the Givat Haviva Art Gallery, explains the uniqueness of the program: "The participants put aside their lives, their homes, not work. They try very hard to get here, and everything takes them very much out of their comfort zone. And then they also create art, which is a very personal thing. They are in a different situation: a common society, a new place, new people, and also a situation of developing a personal process. It's a very exposed place, and many times we feel that we need to give them this space, to get to know each other. There is no better way to get to know each other than to live 24/7 together."

What is your goal?

"To influence the field of art and help people who are graduating from art school. One percent of those who study art go on to become an artist. It's a very difficult statistic, but it's like that all over the world. And in Arab society, much less than that, they continue. Even if they received support from their families in their studies, in the end they say, 'Come on, go back to business,' or 'Get married.' We are engaged in a joint society. We could have launched such a program only to support artists from Arab society, but we believe in connection and sharing. And within this program there is also the idea of promoting Palestinian artists out of a need for correction. The knowledge that they are the contemporary, young, leading force that will carry the correction of what they did not receive in their society."

The Jewish-Arab conflict, Lidror clarifies, is not the issue for which they gathered here. "That's also the strength of the show, I think, that it sits on the ground of art," she explains. "These are artists at the beginning of their careers, who, as far as they are concerned, didn't meet here to talk about the conflict. They met to make art, and they believe in these issues, and in the shared society."

"The issue of languages is something inseparable from my career," says Laila Abdel Razak (26), a multidisciplinary artist from Nof HaGalil. "Because of all the preoccupation and all the philosophical and political problems that are happening around language, it's a very charged matter."

She chose to do her work in the program's shared space through a nature film that explores and critiques the term "coexistence," narrating it in English.

Laila Abdel Razak | Photo: Noga Davis

As a child, Abd al-Razak had a developmental delay in the subject of language because at home she heard three languages – Arabic, Hebrew and English – and she only started speaking at the age of five: "In retrospect, in my generation it was strange, as if it was a kind of betrayal, that I didn't speak Arabic. Because if you're constantly mixing languages, then you've adopted too much Western culture. It affected me socially and politically."

Regarding arriving at the program and the commune life she obliges, she says, "It's no stranger to me, to be with people I don't know. I had to create a certain focus and perspective. The first two weeks were a kind of balancing period – you don't get it, and all kinds of culture shock. I think I was fine most of the time. I had fun discovering that I knew two of the girls who were on the show with me, and I said to myself, at least these are girls I can just unpack with. The point of the show is that we're in a situation where the whole point is to mix and understand each other. A situation that is also intimate within the personal space, and not just the group space. For some it worked out and for some it didn't."

Video Art by Laila Abdel Razaq | Photo: Laila Abd al-Razzaq

What were the difficulties?

"It's funny because some people communicate or function better at different times of the day. There were times when we stayed in the studio until 5 a.m., and then we went back to the rooms, and the roommate woke up and didn't understand the situation."

Have connections been made that you may not have expected to make?

"I flow with everyone. There are people with whom I will be in contact afterwards, and there are those who will not. There are those I connected with, and there are those who didn't, I didn't think I had anything to talk to them about. It's not a national issue."